For all his foresight, even George Orwell would have been astonished at the revolutionary global impact of the first Mac PC in January 1984, says Ron McKay

It’s monochrome, grey on grey, rows of men – worker drones dressed in sackcloth marching in step along a tunnel before filing into a darkened room where the only light comes from a huge screen where a bespectacled Big Brother is chuntering commands. It’s 1984, of course.

The film cuts to a woman athlete running, pursued by helmeted police. By contrast, she is in colour. She’s also wielding a large sledgehammer – she pirouettes and hurls it at the screen which explodes and everything goes to black. Up comes text and a deep male voice intones: “On January 24, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh and you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like 1984.”

It is one of the most famous advertisements in history, screened just once on national television for 100 million Americans watching that year’s Super Bowl. It announced the arrival of the machine which would change history, not just of the industry but our relationship with technology. The Macintosh – the Apple Mac – launched two days later, and brought personal computing to the masses.

Child’s play

IT was so easy to operate that a child could do it. “The big difference with the Mac was that a complete novice – indeed children – 10-year-olds, five-year-olds who had never seen a computer before – seemed to instantly and intuitively lunge for the mouse,” Dag Spicer, senior curator at the Computer History Museum in Palo Alto, California, summed up.

Before the Mac, computers were controlled in a language called DOS by obscure typed-in commands like “copy a:\autoexec.bat c:\windows”, the letters clicking onscreen in white or green on a black background. The industry was largely controlled by IBM – “Big Blue” – with its $5,000 IBM PC XT. At the cheap end there was the Commodore 64 gaming machine, if batting a white, square ball off a digital wall can be considered a game.

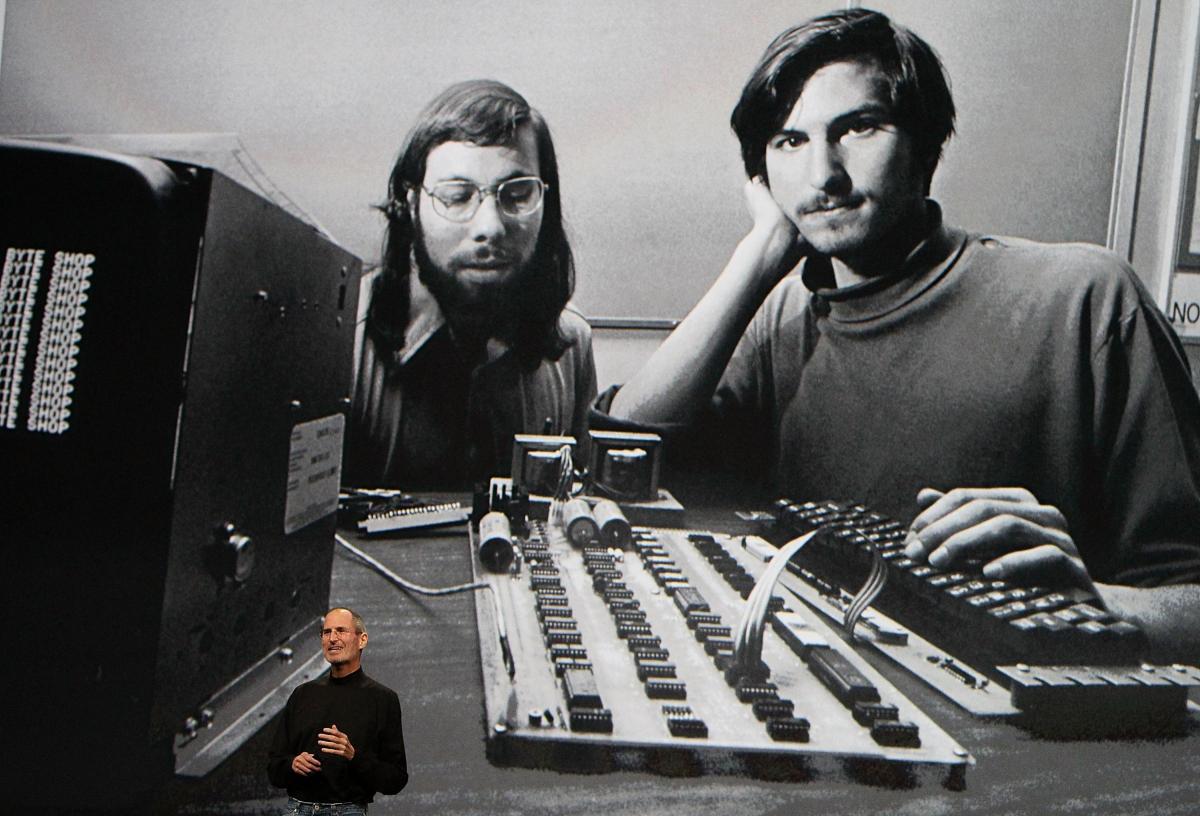

The 30-second launch ad was made by Ridley Scott (with a nod to Fritz Lang’s Metropolis) and the symbolism, the subliminal message, was that the athlete – 19-year-old Anya Major – represented Apple, and Big Brother was the then-dominant IBM. But it nearly didn’t get shown. The Apple board was initially unwilling to fund the $800,000 spot in the showpiece football game and the company’s co-founders, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, had considered funding it themselves.

Wozniak put it this way: “They didn’t like Steve’s [Jobs] personality. Steve would have a vision and they would fight it – they would have a different vision of their own. They just got tired of Steve calling them idiots.”

Eventually, the “idiots” backed down and the ad ran.

Scott the lot

RIDLEY Scott was then the most famous and expensive hired hand making commercials. He would later become a director of blockbuster films including Alien and Blade Runner but he learned his skills in advertising.

For the Apple shoot he demanded an actress capable of running up to a huge computer screen, turning and throwing the hammer convincingly at the screen. Most of the actresses at the casting call, in London’s Hyde Park, couldn’t do it. Indeed, one nearly felled a pedestrian with the hammer. But Major, who was a discus thrower as well as a model, won the role because she could.

The shoot, on the outskirts of London, took three days and the drones, the grim marching men, were local skinheads paid $25 a day.

They were trouble and on the third day they took to fighting and throwing rocks at each other, which didn’t phase Scott. He had what he needed. Two days after the Super Bowl ad the Mac was launched by Jobs to a packed audience in the De Anza College auditorium in Cupertino, still the home of Apple.

Looking at footage now it’s almost like a revivalist meeting, with cheering crowds, people frantically waving arms, gasps, and minutes of applause as the boxy computer is pulled out of a bag by Steve Jobs, who powers it up.

After the swelling music and a few images on the screen, a deep, computer-generated voice comes in: “Hello, I’m Macintosh. It sure is great to get out of that bag. Unaccustomed as I am to public speaking, I’d like to share with you a maxim I thought of the first time I met an IBM mainframe: never trust a computer you can’t lift.”

The audience is frenziedly clapping and cheering. “Obviously, I can talk, but right now I’d like to sit back and listen. So, it is with considerable pride that I introduce a man who’s been like a father to me ... Steve Jobs.”

Opening the Gates

IN the packed audience, near the back of the hall, Bill Gates and a gaggle of Microsoft employees are sitting. They have the message. A year later, in 1985, Microsoft launches the first version of Windows, having licensed some aspects of the interface from Apple.

Three years later, with Windows soaring, Jobs and Apple filed a lawsuit claiming that the look and feel of their software had been copied. The action failed and, since then, graphical interfaces, pioneered by Apple, have become the standard for computers in homes and offices around the world.

Jobs had brought in John Sculley from PepsiCo as chief executive and he was convinced to put around $80 million behind the launch of the Mac. It was a fateful mistake.

Tensions between him and Jobs were evident so much so that the man who, with Wozniak, had started the company in his parents’ garage, joined the small team developing the revolutionary computer, almost as a side project to the main business of the company, which was then the more conventional machines.

Jobs wasn’t just a visionary about computers. He realised that software, and particularly desktop publishing software, would be crucial to success. Adobe’s PostScript Page Description Language, which delivered a uniform computer publishing language and fonts, came with the Mac.

A year after the hysterical launch in Cupertino, in January 1985, Aldus’s Pagemaker debuted on the Mac, along with Mac Publisher and Ready, Set, Go. Jobs’s engineers had also been working on a laser printer and just weeks later the LaserWriter was introduced. Apple had almost single-handedly created the desktop publishing market. The Mac became the favoured machine of graphics departments, marketing divisions, schools, small businesses, and book and newspaper publishers.

The cult of Jobs

STEVE Jobs’s relationship with Sculley was in meltdown, however, and in September 1985 he left, having cashed in stock options of $21.43m. He set up his own computer company, NeXT, which was not the success he imagined. But he did hit the gold seam and become a billionaire by investing in the struggling George Lucas start-up, Pixar Animation Studios, which became stratospherically successful with the film Toy Story.

More than a decade later, in December 1996, Jobs returned to the company he formed when he sold NeXT to Apple for $400m and, after the worst quarter results in its history, became first interim CEO and, shortly after, the permanent boss.

The UNIX-based operating system he developed at NeXT laid the groundwork for the OS X operating system, which Apple continues to develop. The PowerBook, the iMac, the MacBook Air and clutch of computers followed and, in 2007, the product which would take Apple to the top of the corporate ladder and become by far the richest company on the planet, the iPhone. Jobs died of pancreatic cancer in 2011.

Without him and the talking 17lb computer with the nine-inch screen he pulled out of the sack onstage almost 40 years ago, there would have been none of that.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel